The Pleiades

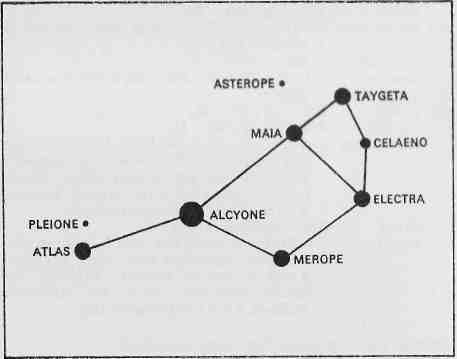

The Pleiades consist of nine named stars, some of them are small stars, the seven sisters; and to these have been added the parents, Atlas (27) and Pleione (28):

Atlas – The father of the Hyades and Pleiades, who was condemned to support the weight of the heavens on his head and hands. Titan bearing up the Heavens. The Endurer. Believed by some mythologists to be the originator of the constellations. Others believe it was Chiron (Centaurus).

Atlas – The father of the Hyades and Pleiades, who was condemned to support the weight of the heavens on his head and hands. Titan bearing up the Heavens. The Endurer. Believed by some mythologists to be the originator of the constellations. Others believe it was Chiron (Centaurus).

Plein – (Pleione, the mother), means `to sail’, making Pleione `sailing queen’ and her daughters `sailing ones.’

Alcyone – Seduced by Poseidon. The Central One. The Hen.

Asterope (Sterope) – Raped by Aries and gave birth to Oenomaus, king of Pisa.

Celæno – Seduced by Poseidon. Was said to be struck by lightning.

Electra – Seduced by Zeus and gave birth to Dardanus, founder of Troy.

Maia – Eldest and most beautiful of the sisters. Seduced by Zeus and gave birth to Hermes. Later became foster-mother to Arcas, son of Zeus and Callisto, during the period while Callisto was a bear, she and Arcas were placed in the heavens by Zeus (she as Ursa Major, Arcas Ursa Minor).

Merope – The missing one or Lost Pleiades. This is the seventh of the sisters. She alone, married a mortal man; Sisyphus, and she repents of it, she hid her face in shame at being the only one not married to a god and from shame at the deed, she alone of the sisters hides herself in the sky (there is some dispute over whether it is Merope or Electra that hides herself, i.e. the star does not shine). Her husband, Sisyphus, son of Æolus, grandson of Deucalion (the Greek Noah), and great-grandson of Prometheus. Sisyphus – Merope’s husband – founded the city of Ephyre (Corinth) and later revealed Zeus’s rape of Ægina to her father Asopus (a river), for which Zeus condemned him to roll a huge stone up a hill in Hades, only to have it roll back down each time the task was nearly done.

Taygete/a – This is the sister who consecrated to Artemis the Cerynitian Hind with the golden horns that Heracles (3rd labor) had to fetch. Seduced by Zeus and gave birth to Lacedæmon, founder of Sparta.

Etymology

Abundant crops and green pastures were attributed to these “Rainy Stars”. They were also connected with traditions of the Flood found among widely separated nations. Their name bears an etymological relationship to the Greek words: pleiôn, meaning “plenty” from pleos, ‘full or many’ from the Indo-European word pel[e]-¹, “to fill”, with derivatives: fill, supply, plenty, accomplish, plethora, complete, plus, plural, replenish, implement, compliment, supplement, police, politics, policy, public, publish, publicity, palm, feeling, folks. (Pokorny 1. pel- 798.)

There are two more suggested derivations for the word Pleiades:

from Greek plein, ‘to sail’, pleusis, ‘sailing’, from Indo-European *pleu– ‘To flow’ (Greek pneuma comes from this root). Pleione is said to mean `sailing one’ and her daughters `sailing ones’, because the helical rising of the group in May marked the opening of navigation to the Greeks because sailing was safe after they had risen; the setting in the late autumn marked the close of navigation.

from peleiades, flock of doves, from Indo-European *pel-2 ‘Pale, dark-colored, gray’, ‘the gray bird’. Some versions made them the Seven Doves that carried ambrosia to the infant Zeus [Star Names]. In Hinduism the Pleiades were the Krittikas, the six nurses of Skanda, the infant god of war, who took to himself six heads for his better nourishment.

The word Pleiades also derives the mother of the Pleiades and Atlas‘ first wife, Pleione, a star that is close to this group. Pleione from Plein,`to sail’, making Pleione “sailing queen” and her daughters “sailing ones.” Ancient Greek sailors were cautioned to sail only during the months when the Pleiades were visible.

The History of the Pleiades

from p.391-412 of Star Names, Richard Hinckley Allen, 1889.

The seven sweet Pleiades above.

— Owen Meredith’s The Wanderer.

The group of sister stars, which mothers love

To show their wondering babes, the gentle Seven.

— Bryant’s The Constellations.

the Narrow Cloudy Train of Female Stars of Manilius, and the Starry Seven, Old Atlas’ Children, of Keats’ Endymion, have everywhere been {Page 392} among the most noted objects in the history, poetry, and mythology of the heavens; though, as Aratos wrote,

not a mighty space

Holds all, and they themselves are dim to see.

All literature contains frequent allusions to them, and in late years they probably have been more attentively and scientifically studied than any other group.

All literature contains frequent allusions to them, and in late years they probably have been more attentively and scientifically studied than any other group.

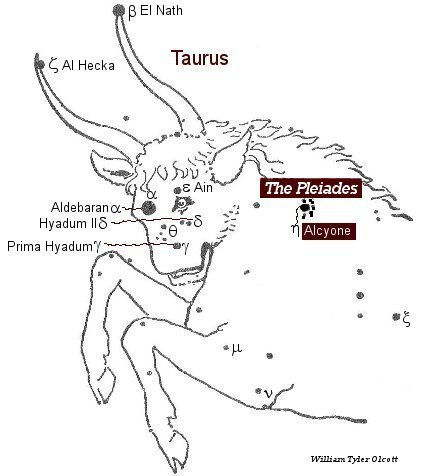

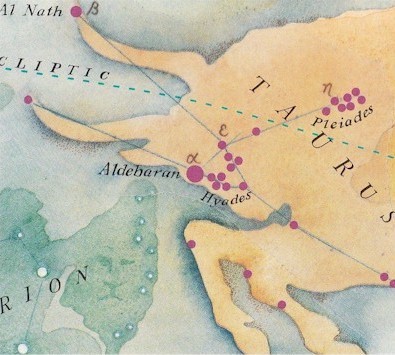

They generally have been located on the shoulder of the Bull as we have them, but Hyginus, considering the animal figure complete, placed them on the hind quarter; Nicander, Columella, Vitruvius, and Pliny, on the tail,

In cauda Tauri septem quas appellavere Vergilias; —

although Pliny also is supposed to have made a distinct constellation of them. Proclus and Geminos said that they were on the back; and others, on the neck, which Bayard Taylor followed in his Hymn to Taurus, where they

Cluster like golden bees upon thy mane.

Eratosthenes, describing them as over the animal, imitated Homer and Hesiod in his Pleias; while Aratos, calling them, in the Attic dialect, Pleiades, placed them near the knees of Perseus; thus, as in most of his poem, following Eudoxos, whose sphere, it is said, clearly showed them in that spot. Hipparchos in the main coincided with this, giving them as Pleias and Pleiades; but Ptolemy used the word in the singular for four of the stars, and did not separate them from Taurus. The Arabians and Jews put them on the rump of Aries; and the Hindu astronomers, on the head of the Bull, where we now see the Hyades.

The Pleiades seem to be among the first stars mentioned in astronomical literature, appearing in Chinese annals of 2357 B.C., Alcyone, the lucida, then being near the vernal equinox, although now 24° north of the celestial equator; and in the Hindu lunar zodiac as the 1st nakshatra, Krittika [Allen notes: The Krittikas were the six nurses of Skanda, the infant god of war, represented by the planet Mars, literally motherless, who took to himself six heads for his better nourishment, and his nurses’ name in Karttikeya, Son of the Krittikas.]Karteek, or Kartiguey, the General of the Celestial Armies, probably long before 1730 B.C., when precession carried the equinoctial point into Aries. Al Biruni, referring to this early position of the equinox in the Pleiades, which he found noticed “in some books of Hermes,” wrote: {Page 393} This statement must have been made about 3000 years and more before Alexander.

And their beginning the astronomical year gave rise to the title “the Great Year of the Pleiades” for the cycle of precession of about 25,900 years.

The Hindus pictured these stars as a Flame typical of Agni, the god of fire and regent of the asterism, and it may have been in allusion to this figuring that the western Hindus held in the Pleiad month Kartik (October-November) their great star-festival Dibali, the Feast of Lamps, which gave origin to the present Feast of Lanterns of Japan. But they also drew them, and not incorrectly, as a Razor with a short handle, the radical word in their title, kart, signifying “to cut.”

The Santals of Bengal called them Sar en; and the Turks, Ulgher.

As a Persian lunar station they were Perv, Perven, Pervis, Parvig, or Parviz, although a popular title was Peren, and a poetical one, Parur. In the Rubais, or Rubdiyat, of the poet-astronomer Omar Khayyam, the tent-maker of Naishapur in 1123, “who stitched the tents of science,” they were Parwin, the Parven of that country to-day; and, similarly, with the Khorasmians and Sogdians, Parvi and Parur; — all these from Peru, the Begetters, as beginning all things, probably with reference to their beginning the year.

In China they were worshiped by girls and young women as the Seven Sisters of Industry, while as the 1st sieu (Moon Mansion) they were Mao, Mau, or Maou, anciently Mol, The Constellation, and Gang, of unknown signification, Alcyone being the determinant.

On the Euphrates, with the Hyades, they seem to have been Mas–tab–ba–gal–gal–la, the Great Twins of the ecliptic, Castor and Pollux (Gemini) being the same in the zodiac.

In the 5th century before Christ Euripides mentioned them with Aetos, our Altair, as nocturnal timekeepers; and Sappho, a century previously, marked the middle of the night by their setting. Centuries still earlier Hesiod and Homer brought them into their most beautiful verse; the former calling them Atlagenes, Atlas-born. The patriarch Job is thought to refer to them twice in his word Kimah, a Cluster, or Heap, which the Hebrew herdsman-prophet Amos, probably contemporary with Hesiod, also used; the prophet’s term being translated “the seven stars” in our Authorized Version, but “Pleiades” in the Revised. The similar Babylonian-Assyrian Kimtu, or Kimmatu, signifies a “Family Group,” for which the Syrians had Kima, quoted in Humboldt’s Cosmos as Gemat; this most natural simile is repeated in Seneca’s Medea as densos Pleiadum greges. Manilius had Glomerabile Sidus, the Rounded Asterism, equivalent to the {Page 394} Globus Pleiadum of Valerius Flaccus; while Brown translates the Pleiades; of Aratos as the Flock of Clusterers.

In Milton’s description of the Creation it is said of the sun that

the gray Dawn and the Pleiades before him danced,

Shedding sweet influence, —

the original of these last words being taken by the poet from the Book of Job, xxxviii, 31, in the Authorized Version, that some have thought an astrological reference to the Pleiades as influencing the fortunes of mankind, or to their presumed influential position as the early leaders of the Lunar Mansions. The Revised Version, however, renders them “cluster,” and the Septuagint by the Greek word for “band,” as if uniting the members of the group into a fillet; others translate it as “girdle,” a conception of their figure seen in Amr al Kais’ contribution to the Muallakat, translated by Sir William Jones:

It was the hour when the Pleiades appeared in the firmament like the folds of a silken sash variously decked with gems.

Von Herder gave Job’s verse as:

Canst thou bind together the brilliant Pleiades ?

Beigel as:

Canst thou not arrange together the rosette of diamonds of the Pleiades ?

and Hafiz wrote to a friend:

To thy poems Heaven affixes the Pearl Rosette of the Pleiades as a seal of immortality.

An opening rose also was a frequent Eastern simile; while in Sadi’s Gulistan, the Rose-garden, we read:

The ground was as if strewn with pieces of enamel, and rows of Pleiades seemed to hang on the branches of the trees;

or, in Graf’s translation:

as though the tops of the trees were encircled by the necklace of the Pleiades.

William Roscoe Thayer repeated the Persian thought in his Halid:

slowly the Pleiades

Dropt like dew from bough to bough of the cinnamon trees.

{Page 395} That all these wrote better than they knew is graphically shown by Miss Clerke where, alluding to recent photographs of the cluster by the Messrs. Henry of Paris, she says:

The most curious of these was the threading together of stars by filmy processes. In one case seven aligned stars appeared strung on a nebulous filament “like beads on a rosary.” The “rows of stars,” so often noticed in the sky, may therefore be concluded to have more than an imaginary existence.

The title, written also Pliades and, in the singular, Plias, has commonly been derived from plein “to sail,” for the heliacal rising of the group in May marked the opening of navigation to the Greeks, as its setting in the late autumn did the close. But this probably was an afterthought, and a better derivation is from pleios, the Epic form of pleos, “full,” or, in the plural, “many,” a very early astronomical treatise by an unknown Christian writer having Plyades a pluralitate. This coincides with the biblical Kimah and the Arabic word for them — Al Thurayya. But as Pleione was the mother of the seven sisters, it would seem still more probable that from her name our title originated.

Some of the poets, among them Athenaeus, Hesiod, Pindar, and Simonides, likening the stars to Rock-pigeons flying from the Hunter Orion, wrote the word Peleiades, which, although perhaps done partly for metrical reasons, again shows the intimate connection in early legend of this group with a flock of birds. When these had left the earth they were turned into the Pleiad stars. Aeschylus assigned the daughters’ pious grief at their father’s (Atlas) labor in bearing the world as the cause of their transformation and subsequent transfer to the heavens; but he thought these Peleiades apteroi, “wingless.” Other versions made them the Seven Doves that carried ambrosia to the infant Zeus, one of the flock being crushed when passing between the Symplegades, although the god filled up the number again. This probably originated in that of the dove which helped Argo through; Homer telling us in the Odyssey that

No bird of air, no dove of swiftest wing,

That bears ambrosia to the ethereal king,

Shuns the dire rocks; in vain she cuts the skies,

The dire rocks meet and crush her as she flies;

and the doves on Nestor’s cup described in the Iliad have been supposed to refer to the Pleiades. Yet some have prosaically asserted that this columbine title is merely from the loosing of pigeons in the auspices customary {Page 396} at the opening of navigation. These stories may have given rise to the Sicilians’ Seven Dovelets, the Sette Palommielle of the Pentameron.

Another title analogous to the foregoing is Butrum from Isidorus, — Caesius wrongly writing it Brutum, — in the mediaeval Latin for Botrus, a Bunch of Grapes, to which the younger Theon likened them. It is a happy simile, although Thompson [Allen notes: He traces the word back as equivalent to oinas, a Dove, probably Columba oenas of Old World ornithology, and so named from its purple-red breast like wine, — oinos, — and naturally referred to a bunch of grapes; or perhaps because the bird appeared in migration at the time of the vintage. This is strikingly confirmed by the fact that coins of Mallos in Cilicia bore doves with bodies formed by bunches of grapes; these coins being succeeded by others bearing grapes alone; and we often see the bird and fruit still associated in early Christian symbolism.] considers it merely another avian association like that seen in the poetical Peleiades and the Alcyone of the lucida.

Vergiliae and Sidus Vergiliarum have always been common for the cluster as rising after Ver, the Spring, — the Breeches Bible having this marginal note at its word “Pleiades” in the Book of Job, xxxviii, 31:

which starres arise when the sunne is in Taurus which is the spring time and bring flowers.

And these names obtained from the times of the Latin poets to the 18th century, but often erroneously written Virgiliae. Pliny, describing the glow-worms, designated them as stellae and likened them to the Pleiades:

Behold here before your very feet are your Vergiliae; of that constellation are they the offspring.

And the much quoted lines in Locksley Hall are similar:

Many a night I saw the Pleiads, rising through the mellow shade, Glitter like a swarm of fire-flies tangled in a silver braid.

Bayer cited Signatricia Lumina.

Hesiod called them the Seven Virgins and the Virgin Stars; Vergil, the Eoae Atlantides; Milton, the Seven Atlantic Sisters; and Hesperides, the title for another batch of Atlas’ daughters from Hesperis, has been applied to them. Chaucer, in the Hous of Fame, had Atlantes doughtres sevene; but his “Sterres sevene” refer to the planets. As the Seven Sisters they are familiar to all; and as the Seven Stars they occur in various early Bible versions; in the Sifunsterri of the Anglo-Saxons, though they also wrote Pliade; in the Septistellium vestis institoris, cited by Bayer; and in the modern German Siebengestirn. This numerical title also frequently has been applied to the brightest stars of the Greater Bear (Ursa Major), as in early days it was to the “seven planets,” — the Sun, Moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. Minsheu had the words” Seven Starres “indiscriminately for {Page 397} the Pleiades, Hyades, and Ursa Major, saying, as to the first,” that appear in a cluster about midheaven.”

As the group outline is not unlike that of the Dipper in Ursa Major, many think that they much more deserve the name Little Dipper than do the seven stars in Ursa Minor; indeed that name is not uncommon for them. And even in our 6th century, with Hesychios, they were Satilla, a Chariot, or Wagon, another well-known figure for Ursa Major.

Ideler mentioned a popular designation by his countrymen, — Schiffahrts Gestirn, the Sailors’ Stars, — peculiarly appropriate from the generally supposed derivation of their Greek title and meteorological character of 2000 years ago; but the Tables of some Obscure Word is of King James I anticipated this in “Seamens Starres — the seaven starres.”

The Teutons had Seulainer; the Gaels, Griglean, Grioglachan, and Meanmnach; the Hungarians, who, Grimm says, have originated 280 native names for stars, called the Pleiades Fiastik and Heteveny, — this last in Finland Het’e wa’ne; the Lapps of Norway knew them as Niedgierreg; while the same people in Sweden had the strange Suttjenes Rauko, Fur in Frost, these seven stars covering a servant turned out into the cold by his master. The Finns and Lithuanians likened them to a Sieve with holes in it; and some of the French peasantry to a Mosquito Net, Cousiniere, — in the Languedoc tongue Cousigneiros. The Russians called them Baba, the Old Wife; and the Poles, Baby, the Old Wives.

As we have seen the Hyades likened to a Boar Throng, so we find with Hans Egede, the first Norse missionary to Greenland, 1721-34, that this sister group was the Killukturset of that country, Dogs baiting a bear; and similarly in Wales, Y twr tewdws, the Close Pack.

Weigel included them among his heraldic constellations as the Multiplication Table, a coat of arms for the merchants.

Sancho Panza visited them, in his aerial voyage on Clavileno Aligero, as las Siete Cabrillas, the Seven Little Nanny Goats; and la Racchetta, the Battledore, is a familiar and happy simile in Italy; but the astronomers of that country now know them as Plejadi, and those of Germany as Plejaden.

The Rabbis are said to have called them Sukkoth Renoth, usually translated “the Booths of the Maidens” or “the Tents of the Daughters,” and the Standard Dictionary still cites this supposed Hebrew title; but Riccioli reversed it as Filiae Tabernaculi. All this, however, seems to be erroneous, as is well explained in the Speaker‘s Commentary on the 2d Book of the Kings xvii, 30, where the words are shown to be intended for the Babylonian goddess Zarbanit, Zirat-banit, or Zir-pa-nit, the wife of Bel Marduk. The Alfonsine Tables say that the “Babylonians,” by whom were probably {Page 398} meant the astrologers, knew them as Atorage, evidently their word for the manzil Al Thurayya, the Many Little Ones, a diminutive form of Tharwan, Abundance, which Al Biruni assumed to be either from their appearance, or from the plenty produced in the pastures and crops by the attendant rains. We see this title in Bayer’s Athoraie; in Chilmead’s Atauria quasi Taurinae; and otherwise distorted in every late mediaeval work on astronomy. Riccioli, commenting on these in his Almagestum Novum, wrote Arabice non Athoraiae vel Atarage sed Altorieh sen Benat Elnasch, hoc est filiae congregationis; the first half of which may be correct enough, but the Benat, etc., singularly confounded the Pleiad stars with those of Ursa Major. In his Astronomia Reformata he cited Athorace and Altorich from Aben Ragel. Turanya is another form, which Hewitt says is from southern Arabia, where they were likened to a Herd of Camels with the star Capella as the driver.

A special Arabic name for them was Al Najm, the Constellation par excellence, and they may be the Star, or the Star of piercing brightness, referred to by Muhammad in the 53d and 86th Suras of the Kuran, and versified from the latter by Sir Edwin Arnold in his At Hafiz, the Preserver:

By the sky and the night star’

By Al Tarik the white star!

To proclaim dawn near;

Shining clear —

When darkness covers man and beast —

the planet Venus being intended by Al Tarik. Grimm cited the similar Syryan Voykodzyun, the Night Star.

They shared the watery character always ascribed to the Hyades, as is shown in Statius’ Pliadum nivosum sidus; and Valerius Flaccus distinctly used the word “Pliada” for the showers, as perhaps did Statius in his Pliada movere; while Josephus states, among his very few stellar allusions, that during the investment of Jerusalem by Antiochus Epiphanes, 170 B.C., the besieged suffered from want of water, but were finally relieved “by a large shower of rain which fell at the setting of the Pleiades.” In the same way they are intimately connected with traditions of the Flood found among so many and widely separated nations, and especially in the Deluge-myth of Chaldaea. Yet with all this well established reputation, we read in the Works and Days:

When with their domes the slow-paced snails retreat,

Beneath some foliage, from the burning heat

Of the Pleiades, your tools prepare.

{Page 399} They were a marked object on the Nile, at one time probably called Chu or Chow, and supposed to represent the goddess Nit or Neith, the Shuttle, one of the principal divinities of Lower Egypt, identified by the Greeks with Athene, the Roman Minerva. Hewitt gives another title from that country, Athurai, the Stars of Athyr (Hathor), very similar to the Arabic word for them; and Professor Charles Piazzi Smyth suggests that the seven chambers of the Great Pyramid commemorate these seven stars.

Grecian temples were oriented to them, or to their lucida; those of Athene on the Acropolis; of different dates, to their correspondingly different positions when rising. These were the temple of 1530 B.C.; the Hecatompedon of 1150 B.C.; and the great Parthenon, finished on the same site 438 B.C. The temple of Bacchus at Athens, 1030 B.C., looked toward their setting, as did the Asclepieion at Epidaurus, 1275 B.C., and the temple at Sunium of 845 B.C. While at some unknown date, perhaps contemporaneous with these Grecian structures, they were pictured in the New World on the walls of a Palenque temple upon a blue background; and certainly were a well-known object in other parts of Mexico, for Cortez heard there, in 1519, a very ancient tradition of the destruction of the world in some past age at their midnight culmination.

A common figure for these stars, everywhere popular for many centuries, is that of a Hen with her Chickens, — another instance of the constant association of the Pleiades with flocking birds, and here especially appropriate from their compact grouping. Aben Ragel and other Hebrew writers thus mentioned them, sometimes with the Coop that held them, — the Massa Gallinae of the Middle Ages; these also appearing in Arabic folk-lore, and still current among the English peasantry. In modern Greece, as the Hencoop, they are Poulia or Pouleia, not unlike the word of ancient Greece. Miles Coverdale, the translator in 1535 of the first complete English Bible, had as a marginal note to the passage in the Book of Job:

these vii starres, the clock henne with her chickens;

and Riccioli, in his Almagestum Novum:

Germanice Bruthean: Anglice Butrio id est gallina fovens pullos.

We see in the foregoing the Butrum of Isidorus, Riccioli’s great predecessor in the Church. The German farm laborers call them Gluck Henne; the Russian, Nasedha, the Sitting Hen; the Danes, Aften Hoehne, the Eve Hen; while in Wallachia they are the Golden Cluck Hen and her five Chicks. In Serbia a Girl is added in charge of the brood, probably the star Alcyone, Maia appropriately taking her place as the Mother. The French and {Page 400} Italians designate them, in somewhat the same way, as Pulsiniere, Poussiniere, and Gallinelle, the Pullets, Riccioli’s Gallinella. Aborigines of Africa and Borneo had similar ideas about them. Pliny’s translator Holland called them the Brood–hen star Vergiliae.

Savage tribes knew the Pleiades familiarly, as well as did the people of ancient and modern civilization; and Ellis wrote of the natives of the Society and Tonga Islands, who called these stars Matarii, the Little Eyes:

The two seasons of the year were divided by the Pleiades; the first, Matarii i nia, the Pleiades Above, commenced when, in the evening, those stars appeared on the horizon, and continued while, after sunset, they were above. The other season, Matarii i raro, the Pleides Below, began when, at sunset, they ceased to be visible, and continued till, in the evening, they appeared again above the horizon.

Gill gives a similar story from the Hervey group, where the Little Eyes are Matariki, and at one time but a single star, so bright that their god Tane in envy got hold of Aumea, our Aldebaran, and, accompanied by Mere, our Sirius, chased the offender, who took refuge in a stream. Mere, however, drained off the water, and Tane hurled Aumea at the fugitive, breaking him into the six pieces that we now see, whence the native name for the fragments, Tauono, the Six, quoted by Flammarion as Tau, both titles singularly like the Latin Taurus. They were the favorite one of the various avelas, or guides at sea in night voyages from one island to another; and, as opening the year, objects of worship down to 1857, when Christianity prevailed throughout these islands. The Australians thought of them as Young Girls playing to Young Men dancing, — the Belt stars of Orion; some of our Indians, as Dancers; and the Solomon Islanders as Togo ni samu, a Company of Maidens. The Abipones of the Paraguay River country consider them their great Spirit Groaperikie, or Grandfather; and in the month of May, on the reappearance of the constellation, they welcome their Grandfather back with joyful shouts, as if he had recovered from sickness, with the hymn, “What thanks do we owe thee ! And art thou returned at last ? Ah ! thou hast happily recovered!” and then proceed with their festivities in honor of the Pleiades’ reappearance.

Among other South American tribes they were Cajupal, the Six Stars.

The pagan Arabs, according to Hafiz, fixed here the seat of immortality; as did the Berbers, or Kabyles, of northern Africa, and, widely separated from them, the Dyaks of Borneo; all thinking them the central point of the universe, and long anticipating Wright in 1750 and Madler in 1846, and, perhaps, Lucretius in the century before Christ.

Miss Clerke, in a charming and instructive chapter in her System of the Stars which should be read by every star-lover, tells us that: {Page 401} With November, the “Pleiad-month,” many primitive people began their year; and on the day of the midnight culmination of the Pleiades, November 17, no petition was presented in vain to the ancient Kings of Persia; the same event gave the signal at Busiris for the commencement of the feast of Isis, and regulated less immediately the celebration connected with the fifty-two-year cycle of the Mexicans. Australian tribes to this day dance in honor of the “Seven Stars,” because “they are very good to the black fellows.” The Abipones of Brazil regard them with pride as their ancestors. Elsewhere, the origin of fire and the knowledge of rice-culture are traced to them. They are the “hoeing-stars” of South Africa, take the place of a farming-calendar to the Solomon Islanders, and their last visible rising after sunset is, or has been, celebrated with rejoicings all over the southern hemisphere as betokening the “waking-up time” to agricultural activity.

They also were a sign to ancient husbandmen as to the seeding-time; Vergil alluding to this in his 1st Georgic, thus rendered by May:

Some that before the fall ‘oth’ Pleiades

Began to sowe, deceaved in the increase,

Have reapt wilde oates for wheate.

And, many centuries before him, Hesiod said that their appearance from the sun indicated the approach of harvest, and their setting in autumn the time for the new sowing; while Aristotle wrote that honey was never gathered before their rising. Nearly all classical poets and prose writers made like reference to them.

Mommsen found in their rising, from the 21st to the 25th of the Attic month Thargelion, May-June, the occasion for the prehistoric festival Plunteria, Athene’s Clothes-washing, at the beginning of the corn harvest, and the date for the annual election of the Achaeans; while Drach surmised that their midnight culmination in the time of Moses, ten days after the autumnal equinox, may have fixed the day of atonement on the 10th of Tishri. Their rising in November marked the time for worship of deceased friends by many of the original races of the South, — a custom also seen with more civilized peoples, notably among the Parsis and Sabaeans, as also in the Druids’ midnight rites of the 1st of November; while a recollection of it is found in the three holy days of our time, All Hallow Eve, All Saints’ Day, and All Souls’ Day.

Hippocrates made much of the Pleiades, dividing the year into four seasons, all connected with their positions in relation to the sun; his winter beginning with their setting and ending with the spring equinox; spring lasting till their rising; the summer, from their appearing to the rising of Arcturus; and the autumn, till their setting again. And Caesar made their heliacal rising begin the Julian summer, and their cosmical setting the commencement of winter. In classic lore the Pleiades were the heavenly group {Page 402} chosen with the sun by Jove to manifest his power in favor of Atreus by causing them to move from east to west.

Notwithstanding, however, all that we read so favorable to the high regard in which these stars were held, they were considered by the astrologers as portending blindness and accidents to sight, a reputation shared with all other clusters. The Arabs, especially, thought their forty days’ disappearance in the sun’s rays was the occasion of great harm to mankind, and Muhammad wrote that “when the star rises all harm rises from the earth.” But Hippocrates had differently written in his Epidemics, a thousand years before, of the connection of the Pleiades with the weather, and of their influence on diseases of autumn:

until the season of the Pleiades, and at the approach of winter, many ardent fevers set in;

and:

in autumn, and under the Pleiades, again there died great numbers.

Although the many legends of their origin are chiefly from Mediterranean countries, yet the Teutonic nations have a very singular one associated with our Savior. It says that once, when passing by a baker’s shop, and attracted by the odor of newly baked bread, He asked for a loaf; but being refused by the baker, was secretly supplied by the wife and six daughters standing by. In reward they were placed in the sky as the Seven Stars, while the baker became a cuckoo; and so long as he sings in the spring, from Saint Tiburtius’ Day, April 14th, to Saint John’s Day, June 24th, his wife and daughters are visible. Following this story, the Pleiades are the Gaelic Crannarain, the Baker’s Peel, or Shovel, a title shared with Ursa Major.

Another, still homelier, but appropriately feminine, name is hinted at in Holland’s translation from the Historia Naturalis, where Pliny treats of “the star Vergiliae”:

So evident in the heaven, and easiest to be known of all others, it is called by the name of a garment hanging out at a Broker’s shop.

Those who have traced out the origin of the title Petticoat Lane for the well-known London street will recognize what Pliny had in mind.

In various ages their title has been taken for noteworthy groups of seven in philosophy or literature. This we see first in the Philosophical Pleiad of 620 to 550 B.C., otherwise known as the Seven Wise Men of Greece, or the Seven Sages, generally given as Bias, Chilo, Cleobulus, Epimenides or {Page 403} Periander, Pittacus, Solon, and the astronomer Thales; again in the Alexandrian Literary Pleiad, or the Tragic Pleiades, instituted in the 3rd century B.C. by Ptolemy Philadelphus, and composed of the seven contemporary poets, variously given, but often as Apollonius of Rhodes, Callimachus or Philiscus, Homer the Younger of Hierapolis in Caria, Lycophron, Nicander, Theocritus, and our Aratos; in the Literary Pleiad of Charlemagne, himself one of the Seven; in the Great Pleiade of France, of the 16th century, brought together in the reign of Henri III, some say by Ronsard, the “Prince of Poets,” others by d’Aurat, or Dorat, the “Modern Pindar,” called “Auratus,” either in punning allusion to his name or from the brilliancy of his genius, and the “Dark Star,” from his silence among his companions; and in the Lesser Pleiade, of inferior lights, in the subsequent reign of Louis XIII. Lastly appear the Pleiades of Connecticut, the popular, perhaps ironical, designation for the seven patriotic poets after our Revolutionary War: Richard Alsop, Joel Barlow, Theodore Dwight, Timothy Dwight, Lemuel Hopkins, David Humphreys, and John Trumbull, — all good men of Yale.

I have not been able to learn when, and by whom, the titles of the seven sisters were applied to the individual stars as we have them; but now they are catalogued nine in all, the parents being included. These last, however, seem to be a comparatively modern addition, the first mention of them that I find — in Riccioli’s Almagestum Novium of 1651 — reading:

Michael Florentius Langrenius illarum exactam figuram observavit, & ad me misit, in qua additae sunt duae Stellae alus innominatae, quas ipse vocal Atlantem, & Pleionem; nescio an sint illae, quas Vendelinus ait observari tanquam novas, quia modo apparent, modo latent.

{p.408}

The Harleian Manuscript of Cicero’s the Greek astronomer Aratus, circa 270 B.C., represents the Sisters by plain female heads under the title VII Pliades et Athlantides, and individually as Merope, Alcyone, Celaeno, Electra, Taygete, Sterope, and Maia. [Other names, too, were assigned to the mythological septette; the scholiast on Theocritus giving them as Coccymo, Plancia, Protis, Parthemia, Lampatho, Stonychia, and the familiar Maia.] Dutch scholar Grotius (1583-1645) has them in the same way, but in far more attractive style, from {p.409} the old Leyden Manuscript, where we find the orthography Asterope and Mea, the former of which, appearing with Germanicus, has become common in our day. The German manuscript, dating from the 15th century, shows seven full-length figures, the Dark Sister smaller than the others, and wearing a dark-blue head-dress, the rest brighter in color, with faces of true German type.

While this list includes all the named Pleiad stars, some practically invisible without optical aid, yet every increase of power reveals a larger number. The Italian astronomer Riccioli wrote about this in 1651:

“Telescopio autem spectatae visae sunt Galileo plus quam 40. ut narratur in Nuncio Sidereo;”

a first-rate field-glass, taking in 3¼° and magnifying seven diameters, shows 57; Hooke, in 1664, saw 78 with the best telescope of his day; Swift sees 300 with his 4 ½-inch, and 600 with his 16-inch; and Wolf catalogued, at the Paris Observatory in 1876, 625 in a space of 90′ by 135′. But with the camera the Messrs. Henry photographed 1421 in 1885, and two years later, by a four-hours’ exposure, 2326 down to the 16th magnitude within three square degrees,— more than are visible at any one time by the naked eye in the whole sky. And a recent photograph by Bailey, with the Bruce telescope, reveals 3972 stars in the region 2° square around Alcyone; although there is no certainty that all of these belong to the Pleiades group. Statements as to their magnitudes and distances make many of them exceed Sirius in size, and to be 250 light years away; but these are based upon an assumption of parallax as yet only hypothetical. But, if correct, how appropriate are Young’s verses in his Night Thoughts:

“How distant some of these nocturnal Suns!

So distant (says the Sage) ’twere not absurd

To doubt, if Beams set out at Nature’s Birth,

Are yet arrived at this so foreign World

Tho’ nothing half so rapid as their Flight;”

and Longfellow’s stanza in his Ode to Charles Sumner;

Were a star quenched on high,

For ages would its light, Still travelling downward from the sky,

Shine on our mortal sight.

While some of these undoubtedly are only optically connected with the true Pleiades, yet the larger part seem to form a more or less united group,{p.410} which the spectroscope shows to be of the same general type; this fact being first brought out by Harvard observers in 1886, from comparisons of the spectra of forty of its stars. They are supposed to be drifting together toward the south-southwest, and so may be called a natural constellation.

Nicander wrote of them as (Greek) olizonas, “the smaller ones”; Manilius (1st century A.D.), as tertia forma, “the third-sized”; and many think that the light of some has decreased, not only from the legends of the Lost Pleiad and the fact that some of the sisters’ names are applied to stars which could not possibly have been seen by the unaided eye, but also because only six are now visible to the average observer, and whoever can see seven can as readily see at least two more. Miss Airy counted twelve; Mr. Dawes, thirteen; and Kepler said that his scholar Michel Mostlin could distinguish fourteen, and had correctly mapped eleven before the invention of the telescope, while others have done about as well; indeed Carl von Littrow has seen sixteen. In the clear air of the tropic highlands more of the group are visible than to us in northern latitudes,— from the Harvard observing station at Arequipa, Peru, eleven being readily seen; so that Willis was unconsciously right in his verses:

“the linked Pleiades Undimm’d are there, though from the sister band The fairest has gone down; and South away!”

The English astronomer Smyth (1788-1865) wrote:

“If we admit the influence of variability at long periods, the seven in number may have been more distinct, so that while Homer and Attalus speak of six, Hipparchus and Aratus may properly mention seven.”

Yet we find Humboldt, in Cosmos, saying that Hipparchos (circa 160-120 B.C.) refuted the assertion of the Greek astronomer Aratus, circa 270 B.C., that only six are to be seen with the naked eye, and that

One star escaped his attention, for when the eye is attentively fixed on this constellation, on a serene and moonless night, seven stars are visible.

But the Greek astronomer Aratus’, circa 270 B.C., words do not justify this statement as to his opinion. He wrote:

“seven paths aloft men say they take,

Yet six alone are viewed by mortal eyes.

From Zeus’ abode no star unknown is lost

Since first from birth we heard,

but thus the tale is told;” { p.411} this “seven paths, (Greek) eptaporoi, being first found in the (Greek) Resos (Rhesos) attributed to Euripides. Alexandrian-Greek astronomer Eratosthenes (276?-196 B.C.) called it (Greek) Pleias eptasteros, the Seven-starred Pleiad, although he described one as (Greek) Panaphanes, All-invisible; Ovid (43 B.C.-18?A.D.) repeated from the Phainomena the now trite

“Quae septem dici, sex tamen esse solent;”

and again:

“Six only are visible, but the seventh is beneath the dark clouds.”

Cicero thought of them in the same way; and Galileo wrote Dico autem sex, quando quidem septima fere nunquam apparet. But the early Copts knew them as Exastron, the Six-starred Asterism, and many Hindu legends mention only six.

Discarding, of course, all the mythical explanations of the Lost Pleiad, I would notice some of the modern and serious attempts at an elucidation of the supposed phenomenon. Doctor Charles Anthon considered it founded solely upon the imagination, and not upon any accurate observation in antiquity. Jensen thinks that, as a favorite object in Babylonia, the astronomers of that country attached to it, with no regard to exactitude, their number of perfection or completeness, 7 playing with them a more important part even than it did among the Jews; thence it descended to Greece, where, its origin being lost sight of, was caused the discrepancy which we cannot now explain, as well as the legends and folk-lore on the subject. Lamb asserted that the astronomers of Assyria could see in their sky seven stars in the group, and so described them; but the Greeks, less favorably situated, finding only six, invented the story of the missing sister. The Italian astronomer Riccioli (1598-1671) propounded a theory—which I have nowhere found adopted by any later writer — that the seventh and missing Pleiad may have been a nova appearing before that number was recorded by observers, but extinguished about the date of the Trojan war; this last idea accounting, too, for the association of Electra with the lost one. Still another explanation is hinted at by Thompson under Coma Berenices; and the really scientific theories of the English astronomer Smyth (1788-1865) and Pickering have already been noticed. It is in these last two, I think, that the solution of this interesting question will be found, if at all; and with the astronomers I would leave it, as perhaps I ought to have done before.

The second-century Greek astronomer Ptolemy mentioned Pleias for only four stars in Tauros that Baily said were Flamsteed’s 18, 19, 23, and 27, our Alcyone singularly being disregarded, as well as four others of our named stars; and the 10th century Persian astronomical writer Al Sufi, who revised Ptolemy’s observations, stated that this “Alexandrian Quartette” also were {p.412} the brightest in his day—the 10th century. But Ulug Beg, although he is supposed to have followed the second-century Greek astronomer Ptolemy, applied “Al Thurayya” to the five that Baily said were Fl. 19, 23, 21, 22, and 25 (Alcyone). Baily himself, editing the 17th century English orientalist Thomas Hyde’s translation of the 15th century Tartar astronomer Ulug Beg, gave only Fl. 19 and 23 as of “Al Thuraja.”

[from p.391-412 of Star Names, Richard Hinckley Allen, 1889.]

The Theoi Project is a good source of information on what has been said about the Pleiades in mythology http://www.theoi.com/Nymphe/NymphaiPleiades.html

The astrological influences of the Pleiades

According to Ptolemy they are of the nature of the Moon and Mars; and, to Alvidas, of Mars, Moon and Sun in opposition. They are said to make their natives wanton, ambitious, turbulent, optimistic and peaceful; to give many journeys and voyages, success in agriculture and through active intelligence; and to cause blindness, disgrace and a violent death. Their influence is distinctly evil and there is no astrological warrant for the oft-quoted passage Job (xxxviii. 31) “Canst thou bind the sweet influences of Pleiades…?” which is probably a mistranslation. [Robson*, p.182.]

A note about the above: It has been said that many of the negative interpretations given by astrologers in the past to the Pleiades and other stars with feminine qualities was caused by prejudice against men with a homosexual leaning. Words like “evil influence”, as in the above case, is likely to relate to homosexuality in men, an unmentionable word in Robson’s days. Other substitutions were: “not a good omen with regard to relationships to the opposite sex”, “disgrace”, “immoral”, “evil disposition”. Homosexuality (in men) is only one of the many likely influences of the Pleiades, but not the predominant influence.

Alcyone causes love, eminence, blindness from fevers, small pox, and accidents to the face. [Robson*, p.119.]

The Pleiades gives ambition and endeavor, which gives preferment, honor and glory. Not a good omen with regard to relationships to the opposite sex. [Fixed Stars and Their Interpretation, Elsbeth Ebertin, 1928, p.26.]

The Pleiades causes bereavement, mourning, sorrows and tragedies. [The Living Stars, Dr. Eric Morse, p.39.]

Pleiades Rising: Blindness, ophthalmia injuries to the eyes and face, disgrace, wounds, stabs (operations nowadays), exile, imprisonment, sickness, violent fevers, quarrels, violent lust, military preferment. If at the same time the Sun is in opposition either to the Ascendant or to Mars, violent death. [Robson*, p.182].

The rising Pleiades are indicative of those who are homosexual, like to be flattered, and (with a poorly positioned Mercury) impudent in speech. When setting this group of star can have just the opposite nature. If aspected by benefics (when setting) the indications are of a pleasant death and if aspected by both malefics and benefics the native is said to be fond of arts and perhaps even become a painter who will acquire great honors in his lifetime. As an example of the fortunate nature of the Pleiades, Josephus, the great Jewish historian (37-100 A.D.), wrote that during the investment of Jerusalem by Antiochus Epiphanes in 170 B.C. the besieged suffered from a severe lack of water but the city was finally relieved “by a large shower of rain which fell at the setting of the Pleiades”. [Fixed Stars and Judicial Astrology, George Noonan, 1990, p.28.]

“The Pleiades, sisters who vie with each other’s radiance. Beneath their influence devotees of Bacchus (god of wine and ecstasy) and Venus (goddess of love) are born into the kindly light, and people whose insouciance runs free at feasts and banquets and who strive to provoke sweet mirth with biting wit. They will always take pains over personal adornment and an elegant appearance they will set their locks in waves of curls or confine their tresses with bands, building them into a thick topknot, and they will transform the appearance of the head by adding hair to it; they will smooth their hairy limbs with the porous pumice, loathing their manhood and craving for sleekness of arm. They adopt feminine dress, footwear donned not for wear but for show, and an affected effeminate gait. They are ashamed of their sex; in their hearts dwells a senseless passion for display, and they boast of their malady, which they call a virtue. To give their love is never enough, they will also want their love to be seen”. [Astronomica, Manilius, 1st century AD, book 5, p.310-313].

Pleiades culminating: Disgrace, ruin, violent death. If with the luminaries it makes its natives military captains, commanders, colonels of horse and emperors. [Robson*, p183.]

Pleiades with Sun: Throat ailments, chronic catarrh, blindness, bad eyes, injuries to the face, sickness, disgrace, evil disposition (used to be a term in astrology for homosexuality), murderer or murdered, imprisonment, death by pestilence, blows, stabs, shooting, beheading or shipwreck. If in 7th house, blindness, especially if Saturn or Mars be with Regulus. If with Mars and Venus the native will be a potent king obeyed by many people but subject to many infirmities. [Robson*, p183.]

Pleiades with Moon: Injuries to the face, sickness, misfortune, wounds, stabs, disgrace, imprisonment, blindness, defective sight especially if in the Ascendant or one of the other angles, may be cross-eyed, Color-blind or the eyes may be affected by some growth. If in the 7th house, total blindness especially if Saturn or Mars be with Regulus and the Moon be combust. [Robson*, p183.]

Pleiades with Mercury: Many disappointments, loss of possessions, much loss from legal affairs, business failure, trouble through children. [Robson*, p183.]

Pleiades with Venus: Immoral, strong passions, disgrace through women, sickness, loss of fortune. [Robson*].

Pleiades with Mars: Many accidents to the head, loss and suffering through fires. If at the same time Saturn is with Regulus, violent death in a tumult. [Robson*, p183.]

Pleiades with Jupiter: Deceit, hypocrisy, legal and ecclesiastical troubles, loss through relatives, banishment or imprisonment. [Robson*, p183.]

Pleiades with Saturn: Cautious, much sickness, tumorous ailments, chronic sickness to family many loses. [Robson*, p184.]

Pleiades with Uranus: Active mind, deformity from birth or through accident in childhood, many accidents and troubles, many unexpected losses often through fire or enemies, marriage partner proves false especially if female, troubles through women, occult interests, unfavorable for children, if any, and lack of harmony with them, heavy losses at end of life, violent death. [Robson*, p184.]

Pleiades with Neptune: Bold, military preferment, honor, wealth, help from friends, many serious accidents, many travel, somewhat dishonorable occupation involving secrecy, ill-health to marriage partner and peculiar conditions respecting parentage, bad for children, may lose everything at end of life, violent death, often abroad while following occupation. [Robson*, p184.]

References:

*[Fixed Stars and Constellations in Astrology, Vivian E. Robson, 1923].