Constellations of Words

Explore the etymology and symbolism of the constellations

the Greater Dog

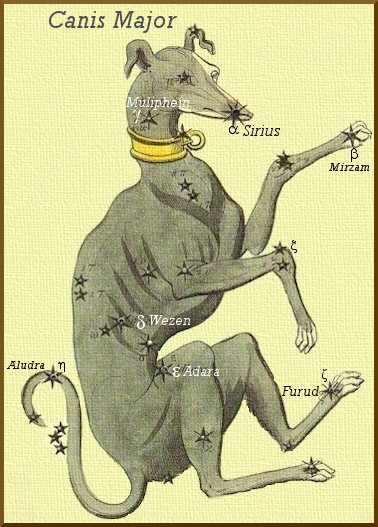

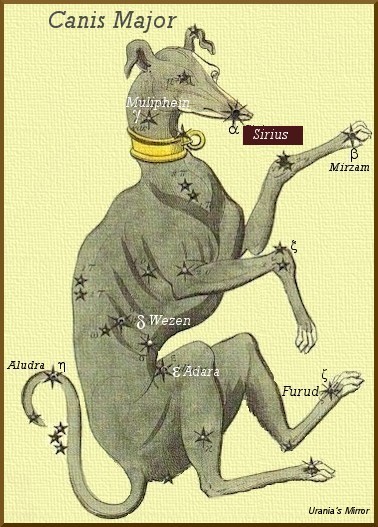

Urania’s Mirror1825

Contents:

1. Clues to the meaning of this celestial feature

2. The fixed stars in this constellation

3. History_of_the_constellation

Clues to the meaning of this celestial feature

This constellation is said to represent the dog set by Jupiter to guard Europa whom he had stolen and conveyed to Crete. According to other accounts, however, it was either Laelaps, the hound of Actaeon; that of Diana’s nymph Procris; that given by Aurora to Cephalus; or finally one of the dogs of Orion. [Fixed Stars and Constellations in Astrology, Vivian E. Robson, 1923, p.34.]

Read the star lore of Sirius by Richard Hinckley Allen (Star Names) here

Read quotes from the ancients on Sirius from the Theoi Project website here

The word Sirius was used interchangeably for both the constellation Canis Major, and the alpha star. Sirius is a Latinized version of Greek seirios, translated ‘scorching’, and signifying brightness and heat, from seiraino, ‘dry up, parch’. Sirius was associated with the hottest part of summer, the Dog Days, and also with causing the Nile floods because the heat causes ice and snow to melt on mountains which flows into rivers. The rising of Sirius marked the commencement of the ancient Egyptian new (sidereal) year, the annus canarius and annus cynicus of the Romans.

Allen in Star Names says the Latins adopted their Canis from the Greeks, sometimes Canicula in the diminutive with the adjectival candens, shining. Varro (p.283) referring to Sirius, says signumcandens, ‘scorching sign’ properly ‘white-hot’. Isidore sees a link with Latin canis, dog, and Latin candere, shining bright:

“The Dog Star (caniculaStella), which is also called Sirius, is in the center of the sky during the summer months. When the Sun ascends to it, and it is in conjunction with the Sun, the Sun’s heat is doubled, and bodies are affected by the heat and weakened. Hence also the ‘dog days’ are named from this star, when purgings are harmful. It is called the ‘Dog’ (canis) Star because it afflicts the body with illness, or because of the brightness (candor) of its flame, because it is of a kind that seems to shine more brightly than the others. It is said they named Sirius so that people might recognize the constellation better” [The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville, 7th century AD, p.105.]

Some authors say that a period of about forty days, beginning three weeks before the annual Sun-Sirius conjunction and ending three weeks after, constituted the ‘dog days’. “They called the period from July 3 to August 11, ‘caniculares dies’ – ‘the Dog Days’” []. Allen in Star Names says that Pliny said the dog days began with the helical rising of of the alpha star of Canis Minor, Procyon (pro-cyon meaning ‘before the dog’), on the 19th of July (Procyon seems to rise two or three days before Sirius []). Nowadays because of precession the dates would be around June 17th to July 27th. “Homer alluded to it in the Iliad as Oporinos, “the Star of Autumn”; but the season intended was the last days of July, all of August, and part of September — the latter part of summer” [Allen Star Names]. In Homer’s time, 8th century BC, the ‘dog days’ would be from July to late August (I think).

Sirius was connected with Isis, or an aspect of Isis, as Allen in Star Names explains: In the earlier temple service of Denderah it was IsisSothis, at Philae IsisSati, or Satit, and, for a long time in Egypt’s mythology, the resting-place of the soul of that goddess, and thus a favorable star. Plutarch made distinct reference to this; although it should be noted that the word Isis at times also indicated anything luminous to the eastward heralding sunrise [Allen, Star Names, Sirius]. “In the Lamentations of Isis and Nephthys, from a fourth century BC papyrus, Isis asserts that she is Sothis (Sirius), who will unswervingly follow Osiris in his manifestation as Orion in heaven” [].

The word siriasis, means sunstroke, from Greek seirian, ‘hot, scorching’, from Greek seirios. Klein [Comprehensive Etymological Dictionary] relates siriasis to the word seismo-, and explains; “seismo-, Greek seismo, ‘earthquake’, from Greek seiein, ‘to shake, move to and fro’, which stands for *tweisein, from Indo-European base *tweis-, ‘to shake; move violently’, whence also Old Indian tvesati, tvesah, ‘vehement, impetuous; shining, brilliant’. Compare siriasis, Sirius, sistrum“. Seismo- and sistrum, a rattle used in ancient Egypt in the worship of Isis, comes from the Indo-European root *twei– ‘To agitate, shake, toss’. Extended form *tweid-; whittle (from Old English thwitan, to strike, whittle down), doit (from Middle Dutch duit, a small coin < ‘piece cut or tossed off’ from Germanic *thwit-). Extended form *tweis-; seism (quake, from Gk. seismos ‘earthquake’ from seiein ‘to shake’), seismo-, sistrum. [Pokorny 2. twei– 1099 Watkins

“The ‘barcoo dog,’ a sheep herding tool used in Australian bush band music, is a type of sistrum” []. “Plutarch says of the sistrum, that the shaking of the four bars within the circular apsis represented the agitation of the four elements within the compass of the world, by which all things are continually destroyed and reproduced” []. An earthquake results from the sudden release of stored energy in the Earth’s crust that creates seismic waves.

“Sistrums (sistrum, i.e. a kind of metallic rattle) are named after their inventor, for Isis, an Egyptian queen, is thought to have invented this type of instrument. Juvenal says (Satires 13.93): ‘May Isis strike my eyes with her angry sistrum. Whence women play these instruments, because the inventor of this type of instrument was a woman. Whence also it is said that among the Amazons, the army of women was summoned to battle by sistrums’” [The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville, 7th century AD, p.98.]

“Homer compares Achilles to the autumnal star, whose brilliant ray shines eminent amid the depth of night, whom men the dog-star of Orion call” [Allen Star Names].

“Meanwhile, old Priam was the first to catch sight of Achilles, as he dashed across the plain, blazing like that star which comes at harvest time— its light shines out more brightly than any of the countless lights in night’s dark sky. People call this star by the name Orion‘s Dog. It is the brightest of the stars, but an unwelcome sign, for it brings wretched mortals many fevers. The bronze on Achilles‘ chest glittered like that star, as he ran forward”. [Homer, Iliad 22.25-31 http://www.mala.bc.ca/~johnstoi/homer/iliad22.htm ]

The bravest of the Greek heroes in the war against the Trojans, Achilles was eventually killed by a poisoned arrow that hit his heel, the only vulnerable part of his body. We get the term ‘achillesheel‘ from his name. Dogs do not have heels but they do have achilles tendons. Dogs follow in the heels of their owners. Sirius, one of Orion’s dogs, is positioned under the heel of Orion. “Isis asserts that she is Sothis (Sirius), who will unswervingly follow Osiris in his manifestation as Orion in heaven” [10]. The ‘Dog Days’ represents the time when the Sun joins Sirius, afterwards the Sun and Sirius part company. Achilles was without his friend Patroclus who was killed in the Trojan war (dogs are man’s best friends) and Achilles sought revenge. The theme here is separation which might confirm what some believe the meaning of the Greek prefix a-, ‘without’, in Achilles name. The Latin suffix –chilles, Greek -khilleus, might have a number of meanings, one suggestion being Greek kheilos, lip. Helios or Elios, is the Greek word for the Sun, Latin Helius, cognate with Breton heol, Welsh haul, Old Cornish heuul. These Celtic cognates of Helios resemble the word ‘heel’, and resemble the latter part of the name Achilles (ac-hiles) or Akhilleus (ak-hilius)…? The Latin (of ac-) or Greek might be silent, making the word; ‘without the Sun’? or ‘without the heel’; or the ac– could be a variant of ad– (as in the prefix accede) meaning ‘near to’ or ‘to, near, at’ – ‘near the Sun’.

The ancient Egyptian sidereal year began when Sirius could be seen in the east at dawn [11]. The usual Latin word for ‘star’ is ‘stella‘. There is another Latin word that is translated ‘star’; sidus, which also seems to have meant ‘Sirius’. [Latin sidereus (sidereal), with the letter dropped, gives sierius, like Greek seirios, Latinized to seirius, then sirius; Latin Sirius is from Greek Seirios. Sirius might have the actual meaning ‘sideral’.]

Sidus, especially Sirius or the Dog’s star, whence “sidere percussus” is, blighted or blasted, and sideratus. [An etymological dictionary of the Latin language, Valpy, 1828, p.431]

Latin sidus comes from the Indo-European root *sweid To shine. Possible suffixed form *sweides-. 1. sidereal, from Latin sidus, constellation, star. 2. consider (“set alongside the stars”), considerate, desire (Latin desiderare, from de + sidus, the meaning of “await what the stars will bring”), 3. Possible variant form *sweid-. swidden (an area cleared for temporary cultivation by cutting and burning the vegetation), from Old Norse svidha, to be singed. [Pokorny I. sueid– 1042.]

Because Sirius (the main star in Canis Major) and Procyon (the main star in Canis Minor) are seen on opposite sides of the Milky Way, there is an Arab story describing how these two companions became separated by the great Sky River. The Arabs tell of two sisters who tried to follow their brother Suhail (Canopus) across the sky. When they came to the great Sky River they plunged in to swim across. The older and stronger sister (Sirius) managed and today can be seen on the southern bank of that great river. But the younger sister was too weak and remained weeping on the northern bank, where we still see her today as Procyon, or Canis Minor

The astrological influences of the constellation given by Manilius:

It is Orion who leads the constellations as they speed over the full circuit of the heavens. At his heels follows the Dog outstretched in full career: no star comes on mankind more violently or causes more trouble when it departs. Now it rises shivering with cold, now it leaves a radiant world open to the heat of the Sun [translator’s note: In ancient times the Dogstar’s evening rising occurred in early January, its evening setting in early May]: thus it moves the world to either extreme and brings opposite effects. Those who from Mount Taurus’ lofty peak observe it ascending when it returns at its first rising learn of the various outcomes of harvests and seasons, what state of health lies in store, and what measure of harmony. It stirs up war and restores peace, and returning in different guise affects the world with the glance it gives it and governs with its mien. Sure proof that the star has this power are its colour and the quivering of the fire that sparkles in its face. Hardly is it inferior to the Sun, save that its abode is far away and the beams it launches from its sea-blue face are cold. In splendour it surpasses all other constellations, and no brighter star is bathed in ocean or returns to heaven from the waves. [Manilius, Astronomica, 1st century AD, book 1, p.34-37]

“The brilliant constellation of the Dog: it barks forth flame, raves with its fire, and doubles the burning heat of the Sun. When it put its torch to the earth and discharges its rays, the earth foresees its conflagration and tastes its ultimate fate [translator’s note: the ecpyrosis of the Stoics, who held that the Universe would ultimately be engulfed in conflagration and all things would return to the condition of primeval fire].

“Neptune lies motionless in the midst of his waters and the green blood is drained from leaves and grass. All living things seek alien climes and the world looks for another world to repair to; beset by temperatures too great to bear, nature is afflicted with a sickness of its own making, alive, but on a funeral-pyre: such is the heat diffused among the constellations, and everything is brought to a halt by a single star. When the Dogstar rises over the rim of the sea, which at its birth not even the flood of Ocean can quench, it will fashion unbridled spirits and impetuous hearts; it will bestow on its sons billows of anger, and draw upon them the hatred and fear of the whole populace.

“Words run ahead of the speakers: the mind is too fast for the mouth [translator’s note: the impetuosity of the speaker causes him to utter words before he has time to adapt them to grammar or logic]. Their hearts start throbbing at the slightest cause, and when speech comes their tongues rave and bark, and constant gnashing imparts the sound of teeth to their utterance. Their failings are intensified by wine, for Bacchus [alcohol] gives them strength and fans their savage wrath to flame.

“No fear have they of woods or mountains, or monstrous lions, the tusks of the foaming boar, or the weapons which nature has given wild beasts; they vent their burning fury upon all legitimate prey.

“Lest you wonder at these tendencies under such a constellation, you see how even the constellation itself hunts among the stars, for in its course it seeks to catch the Hare (Lepus) in front.” [Manilius, Astronomica, 1st century AD, book 5, p.316-319].

© Anne Wright 2008.

| Fixed stars in Canis Major | |||||||

| Star | 1900 | 2000 | R A | Decl 2000 | Lat | Mag | Sp |

| Mirzam beta (β) | 05CAN48 | 07CAN11 | 6h 22m 42s | -17° 57′ 21″ | -41 15 36 | 1.99 | B1 |

| Furud zeta (ζ) | 05CAN59 | 07CAN23 | 6h 20m 18.8s | -30° 3′ 48″ | -53 22 45 | 3.10 | B5 |

| Sirius alpha (α) | 12CAN42 | 14CAN05 | 6h 45m 8.9s | -16° 42′ 58″ | -39 35 38 | -1.40 | A1 |

| Muliphein gamma (γ) | 18CAN13 | 19CAN36 | 7h 3m 45.5s | -15° 38′ 0″ | -37 59 59 | 4.10 | B8 |

| Adara epsilon (ε) | 19CAN22 | 20CAN46 | 6h 58m 37.5s | -28° 58′ 20″ | -51 21 58 | 1.50 | B1 |

| omicron (ο) | 19CAN37 | 21CAN00 | 7h 3m 1.5s | -23° 50′ 0″ | -46 08 11 | 3.12 | B3 |

| Wezen delta (δ) | 22CAN00 | 23CAN24 | 7h 8m 23.5s | -26° 23′ 36″ | -48 27 32 | 1.98 | G3 |

| Aludra eta (η) | 28CAN09 | 29CAN32 | 7h 24m 5.7s | -29° 18′ 11″ | -50 36 51 | 2.43 | B5 |

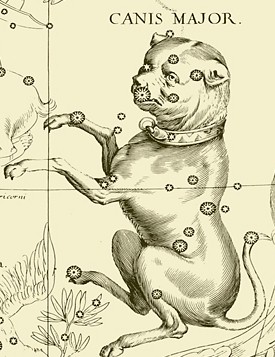

Hevelius,Firmamentum, 1690

History of the constellation

from Star Names: Their Lore and Meaning, 1889, Richard H. Allen

Fierce on her front the blasting Dog-star glowed.

— Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s OftIkeFrenchRevolution

One blazes through the brief bright summer’s length,

Lavishing life-heat from a flaming car.

— Christina G. Rossetti’s LaterLife

CanisMajor, the Greater Dog of the southern-heavens, and thus CanisAustralior, lies immediately to the southeast of Orion, cut through its centre by the Tropic of Capricorn, and with its eastern edge on the Milky Way.

It is CaneMaggiore in Italy; Caes in Portugal; GrandChien in France; and GrosseHund in Germany.

In early classical days it was simple Canis, representing Laelaps, the hound of Actaeon, or that of Diana’s nymph Procris, or the one given to Cephalus by Aurora and famed for the speed that so gratified Jove (Jupiter, Zeus) as to cause its transfer to the sky. But from the earliest times it also has been the Dog of Orion to which Aratos alluded in the Prognostica, and thus wrote of in the Phainomena in connection with the Hare (Lepus):

The constant Scorcher comes as in pursuit,

. . . and rises with it and its setting spies.

Homer made much of it as Kuon, but his Dog doubtless was limited to the star Sirius, as among the ancients generally till, at some unknown date, the constellation was formed as we have it, — indeed till long afterwards, for we find many allusions to the Dog in which we are uncertain whether the constellation or its lucida (alpha star Sirius) is referred to. Hesiod and Aratos gave this title, both also saying Seirios, and the latter megas (meaning major or big); but by this adjective he designed only to characterize the brilliancy of the star, and not to distinguish it from the Lesser Dog (Canis Minor). The Greeks did not know the two Dogs thus, nor did the comparison appear till the days of the Roman Vitruvius.

{Page 118} Ptolemy and his countrymen knew it [the constellation] by Homer’s title, and often as Astrokuon (dogstar), although it seems singular that the former never used the word Seirios

The Latins adopted their Canis from the Greeks, and it has since always borne this name, sometimes even Canicula in the diminutive (with the adjectival candens, shining), Erigonaeus (from Virgo), and Icarius (from Bootes); the last two being from the fable of the dog Maera, — which itself means Shining, — transported here; her mistress Erigone having been transformed into Virgo, and her master Icarius into Bootes. Ovid alluded to this in his Icariistellaprotervacanis; and Statius mentioned the Icariumastrum, although Hyginus had ascribed this to the Lesser Dog (Canis Minor).

Sirion and Syrius occasionally appeared with the best Latin authors; and the AlfonsineTables of 1521 had CanisSyrius

Vergil brought it into the 1st Georgic as a calendar sign, —

adverse cedens Canis occidit astro, —

instructing the farmer to sow his beans, lucerne, and millet at its heliacal setting on the 1st of May; the adverse here generally being referred to the well-known reversed position of the figure of Taurus, but may have been intended to indicate the hostility of the Bull to the Giant’s Dog that was attacking him.

Custos Europae is in allusion to the story of the Bull who, notwithstanding the Dog’s watchfulness, carried off that maiden; and JanitorLethaeus, the Keeper of Hell, makes him a southern Cerberus, the watch-dog of the lower heavens, which in early mythology were regarded as the abode of demons: a title more appropriate here than for the so-named modern group in the northern, or upper, sky.

Bayer erroneously quoted as proper names Dexter, Magnus, and Secundus, while others had Alter and Sequens; but these originally were designed only to indicate the Dog’s position, size, and order of rising with regard to his lesser companion.

The aestifer of Cicero and Vergil referred to its bright Sirius as the cause of the summer’s heat, which also induced Horace’s invidumagricolis; and Bayer’s Udrophobia (hydrophobia, fear of water, a term for rabies), was from the absurd notion, prevalent then as now, of the occurrence of canine madness solely during the heat from the Dog-star: an idea first seen with Asclepiades of the 3rd century before Christ. Or it may have come from being confounded by Bayer, none too careful a compiler, with the Udragogon, which Plutarch applied to Sirius in his DeIsidore, signifying the Water-bringer, i.e. the cause of the Nile flood.

{Page 119} Aratos termed the constellation poikilos, as of varying brightness in its different parts; or mottled — the Dog, lying in as well as out of the Milky Way, being thus diversified in light.

In early Arabia, as indeed everywhere, it took titles from its lucida, although strangely corrupted from the original AlShi’raal ‘AburalYamaniyyah, the Brightly Shining Star of Passage of Yemen, in the direction of which province it set. Among these we see, in the LatinAlmagest of 1515, “canis: etestasehere, alahaboraliemenia“; in the edition of 1551, Elscheere; in Bayer’s Uranoinetria, Elseiri (which Grotius derived from seirios), Elsere, Sceara, Scera, Scheereliemini; in Chilmead’s Treatise, Alsaharealiemalija; and Elchabar, which La Lande, in his Astronomic, not unreasonably derived from Al Kabir, the Great.

The Arabian astronomers called it AlKalbalAkbar, the Greater Dog, so following the Latins, Chilmead writing it AlchelebAlachbar; and Al Biruni quoted their AlKalbalJabbar, the Dog of the Giant, directly from the Greek conception of the figure. Similarly it was the Persians’ KelboGavoro

It was, of course, important in Euphratean astronomy, and is shown on remains from the temples and mounds, variously pictured, but often just as Aratos described it and as drawn on maps of the present day, — standing on the hind feet, watching or springing after the Hare (Lepus). Professor Young describes the figure as one “who sits up watching his master Orion, but with an eye out for Lepus.”

Bayer and Flamsteed alone among its illustrators showed it as a typical bulldog.

A Dog, presumably this with another adjacent, is represented on an ivory disc found by Schliemann on his supposed site of Troy; and an Etruscan mirror of unknown age bears it with Orion, Lepus, the crescent moon, and correctly located neighboring stars. While both of the Dogs (this constellation Canis Major and Canis Minor), the Dragon (Draco), Fishes (Pisces), Swan (Cygnus), Perseus, the Twins (Gemini), Orion, and the Hare (Lepus) are described as on the Shield of Hercules in the old poem of that title generally attributed to Hesiod. The Hindus knew it as Mrigavyadha, the Deer-slayer, and as Lubdhaka, the Hunter, who shot the arrow, our Belt of Orion, into the infamous Praja-pati (identified with Orion), where it even now is seen sticking in his body; and, much earlier still, with their prehistoric predecessors it was Sarama, one of the Twin Watch-dogs of the Milky Way.

Among northern nations it was Greip, the dog in the myth of Sigurd.

All of these doubtless referred solely to Sirius

Novidius, who imagined biblical significance in every starry group, said that this was the DogofTobias in the BookofTobit, v, 16, which Moxon {Page120} confirmed “because he hath a tayle,” and for that reason only; but Julius Schiller, another of the same school, saw here the royal SaintDavid. Gould catalogued 178 stars down to the 7th magnitude.

Hail, mighty Sirius, monarch of the suns !

May we in this poor planet speak with thee ?

— Mrs. Sigourney’s TheStars

Star Names: Their Lore and Meaning, Richard H. Allen, 1889.]

The history of Sirius the Dog-star

from p.129 of Star Names, Richard Hinckley Allen, 1889.

[A scanned copy can be viewed on this webpage

Sirius, the Dog-star, often written Syrius even as late as Flamsteed’s and Father Hell’s day, has generally been derived from Seirios, sparkling or scorching, which first appeared with Hesiod as a title for this star, although also applied to the sun, and by Abychos to all the stars. Various early Greek authors used it for our Sirius, perhaps generally as an adjective, for we read in Eratosthenes:

Such stars astronomers call seirious on account of the tremulous motion of their light;

so that it would seem that the word, in its forms seir, seiros, and seirios, — Suidas used all three for both sun and star, — originally was employed to indicate any bright and sparkling heavenly object, but in the course of time became a proper name for this brightest of all the stars. Lamb, however, thought it of Phoenician origin, signifying the Chief One, and originally in that country a title for the sun; Jacob Bryant, the mythologist, said that it was from the Egyptians’ Cahen Sihor; but Brown considers it a transcription from their well-known Hesiri, the Greek Osiris; while Dupuis distinctly asserted that it was from the Celtic Syr

Plutarch called it Prooptes, the Leader,which well agrees with its character and is an almost exact translation of its Euphratean, Persian, Phoenician, and Vedic titles; kuon, kuon seirios, kuon aster, Seirios aster, Seirios astron, or simply to astron, were its names in early Greek astronomy and poetry. Prokuon, better known for the Lesser Dog (Canis Minor) and its lucida (Procyon), also was applied to Sirius by Galen as preceding the other stars in the constellation.

Homer alluded to it in the Iliad as Oporinos, the Star of Autumn; [The Greeks had no word exactly equivalent to our “autumn” until the 5th century before Christ, when it appeared in writings ascribed to Hippocrates.] but the season intended was the last days of July, all of August, and part of September — the latter part of summer. Lord Derby translated this celebrated passage:

A fiery light

There flash’d, like autumn’s star, that brightest shines

When newly risen from his ocean bath;

{Page 121} while later on in the poem Homer compares Achilles, when viewed by Priam, to the autumnal star, whose brilliant ray

Shines eminent amid the depth of night,

Whom men the dog-star of Orion call.

The Roman farmers sacrificed to it a fawn-colored dog at their three festivals when, in May, the sun began to approach Sirius. These, instituted 238 B.C., were the Robigalia, to secure the propitious influence of their goddess Robigo in averting rust and mildew from their fields; and the Floralia and Vinalia, to ensure the maturity of their blooming flowers, fruits and grapes.

Among the Latins it naturally shared the constellation’s titles, probably originated them; and occasionally was even Canicula; indeed, as late as 1420 the Palladium of Husbandry urged certain farm-work to be done “Er the caniculere, the hounde ascende” and, more than a century later, Eden, in the Historic of the Vyage to Moscovie and Cathay, wrote: “Serius is otherwise called Canicula, this is the dogge, of whom the canicular days have their name.”

It has been asserted that Ovid and Vergil referred to Sirius in their Latrator Anubis, representing a jackal, or dog-headed Egyptian divinity, guardian of the visible horizon and of the solstices, transferred to Rome as goddess of the chase; but it is very doubtful whether they had in mind either star or constellation.

Its well-known name, Al Shi’ra, or Al Si’ra, extended as al Abur al Yamaniyyah, much resembles the Egyptian, Persian, Phoenician, Greek, and Roman equivalents, and, Ideler thought, may have had common origin with them from some one ancient, source: possibly the Sanskrit Surya, the Shining One, — the Sun. The ‘Abur, or Passage, refers to the myth of Canopus’ flight, to the South; and the adjective to the same, or perhaps to the southerly position of the star towards Yemen, in distinction from that of Al Ghumaisa’ in the Lesser Dog, seen towards Sham, — Syria, — in the North. From these geographical names originated the Arabic adjectives Yamaniyyah and Shamaliyyah, Southern and Northern; although the former literally signifies On the Right-hand Side, i.e. to an observer facing eastward towards Mecca.

In Chrysococca’s Tables the title is Siaer Iamane; and Doctor C. Edward Sachau’s translation of Al Biruni’s Chronology renders it Sirius Jemenicus. Riccioli had Halabor, which the 1515 Almagest applied to the constellation; and English writer on globes John Chilmead (circa 1639), Gabbar, Ecber, and Habor; while Shaari lobur, another {Page 122} queerly corrupted form, is found in Eber’s EgyptianPrincess. In the Alfonsine Tables the original is changed to Asceher and Aschere Aliemini; while Bayer gives plain Aschere and Elscheere for the star, with others similar for both star and constellation. Scera is cited by Dutch scholar Grotius (1583-1645) for the star, and Sceara for the whole, derived from an old lexicon; and Alsere; but he traced all to Seirios

In modern Arabia it is Suhail, the general designation for bright stars. The late Finnish poet Zakris Topelius accounted for the exceptional magnitude of Sirius by the fact that the lovers Zulamith the Bold and Salami the Fair, after a thousand years of separation and toil while building their bridge, the Milky Way, upon meeting at its completion,

Straight rushed into each other’s arms

And melted into one;

So they became the brightest star

In heaven’s high arch that dwelt —

Great Sirius, the mighty Sun

Beneath Orion’s belt.

The native Australians knew it as their Eagle, a constellation by itself (Aquila); while the Hervey Islanders, calling it Mere, associated it in their folklore with Aldebaran and the Pleiades.

Sharing the Sanskrit titles for the whole, it was the Deer-slayer and the Hunter, while the Vedas also have for it Tishiya or Tishiga, Tistrija, Tishtrya, the Tistar, or Chieftain’s Star. And this we find too in Persia; as also Sira. The later Persian and Pahlavi have Tir, the Arrow. Edkins, however, considers Sirius, or Procyon, to be Vanand, and Arcturus, Tistar.

Hewitt sees in Sirius the Sivanam, or Dog, of the RigVeda awakening the Ribhus, the gods of mid-air, who “thus calls them to their office of rain sending,” a very different office from that assigned to this star in Rome. Yet these gods, philologically, had a Roman connection, for Professor Friedrich Maximilian Mueller, writing the word Arbhu, associates it with the Latin Orpheus. Hewitt also says that in the earliest Hindu mythology Sirius was Sukra, the Rain-god, before Indra was thus known; and that in the Avesta it marked one of the Four Quarters of the Heavens.

Although the identification of Euphratean stellar titles is by no means settled, especially and singularly so as to this great star, yet various authorities have found for it names more or less probable.

Berlin and Brown think it conclusively proved that it was Kak-shisha, the Dog that Leads, and “a Star of the South” while Kak-shidi is Sayce’s transliteration of the original signifying the Creator of Prosperity, a character which the Persians also assigned to it; and it may have been the {Page 123} Akkadian Du-shisha, the Director — in Assyrian Mes-ri-e. Epping and Strassmaier have Kak-ban as a late Chaldaean title, which Brown renders Kal-bu, the Dog, “exactly the name for Sirius we should expect to find” German Orientalist Peter Jensen (1861-1936) has Kakkab lik-ku, the Star of the Dog, revived in Homer’s kuon; and it perhaps was the Assyrian Kal-bu Sa-mas, the Dog of the Sun; and the Akkadian Mul-lik-ud, the Star Dog of the Sun. Jensen also gives Kakkab kasti, the Bow Star, although this may be doubtful; and Brown has, from the Assyrian, Su-ku-du, the Restless, Impetuous, Blazing, well characterizing the marked scintillation and color changes in its light. Hewitt cites an Akkadian title Tis-khu

Its risings and settings were regularly tabulated in Chaldaea about 300 B.C., and Oppert is reported to have recently said that the Babylonian astronomers could not have known certain astronomical periods, which as a matter of fact they did know, if they had not observed Sirius from the island of Zylos in the Persian Gulf on Thursday, the 29th of April, 11542 B.C.!

It is the only star known to us with absolute certitude in the Egyptian records — its hieroglyph, a dog, often appearing on the monuments and temple walls throughout the Nile country. Its worship, chiefly in the north, perhaps, did not commence till about 3285 B.C., when its heliacal rising at the summer solstice marked Egypt’s New Year and the beginning of the inundation, although precession has now carried this rising to the 10th of August. At that early date, according to Lockyer, Sirius had replaced gamma Draconis as an orientation point, especially at Thebes, and notably in the great temple of Queen Hatshepsu, known to-day as Al Der al Bahari, the Arabs’ translation of the modern Copts’ (who are now the Christians in Egypt) Convent of the North. Here it was symbolized, under the title of Isis Hathor, by the form of a cow with disc and horns appearing from behind the western hills. With the same title, and styled Her Majesty of Denderah, it is seen in the small temple of Isis, erected 700 B.C., which was oriented toward it; as well as on the walls of the great Memnonium, the Ramesseum, of Al Kurneh at Thebes, probably erected about the same time that this star’s worship began. Lockyer thinks that he has found seven temples oriented to the rising of Sirius. It is also represented on the walls of the recently discovered step-temple of Sakkara, dating from about 2700 B.C., and supposed to have been erected in its honor.

Great prominence is given to it on the square zodiac of Denderah, where it is figured as a cow recumbent in a boat with head surmounted by a star; and again, immediately following, as the goddess Sothis, accompanied by the goddess Anget, with two urns from which water is flowing, emblematic {Page 124} of the inundation at the rising of the star. But in the earlier temple service of Denderah it was Isis Sothis, at Philae Isis Sati, or Satit, and, for a long time in Egypt’s mythology, the resting-place of the soul of that goddess, and thus a favorable star. Plutarch made distinct reference to this; although it should be noted that the word Isis at times also indicated anything luminous to the eastward heralding sunrise. Later it was Osiris, brother and husband of Isis, but this word also was applied to any celestial body becoming invisible by its setting. Thus its titles noticeably changed in the long period of Egypt’s history.

As Thoth, and the most prominent stellar object in the worship of that country, — its heliacal rising was in the month of Thoth, — it was in some way associated with the similarly prominent sacred ibis, also a symbol of Isis and Thoth, for, in various forms, the bird and star appear together on Nile monuments, temple walls, and zodiacs.

Sirius was worshiped, too, as Sihor, the Nile Star, and, even more commonly, as Sothi and Sothis, its popular Graeco-Egyptian name, the Brightly Radiating One, the Fair Star of the Waters; but in the vernacular was Sept, Sepet, Sopet, and Sopdit; Sed [According to Mueller, this Sed, or Shed, of the hieroglyphic inscriptions appeared in Hebrew as El Shaddar.] and Sot, — the Seph of Vettius Valens.

Upon this star was laid the foundation of the Canicular, Sothic, or Sothiac Period named after it, which has excited the attention and puzzled the minds of historians, antiquarians, and chronologists. Lockyer has an admirable discussion of this in his Dawn of Astronomy

Sir Edwin Arnold writes of it in his Egyptian Princess

And even when the Star of Kneph has brought the summer round,

And the Nile rises fast and full along the thirsty ground;

for the Egyptians always attributed to the Dog-star the beneficial influence of the inundation that began at the summer solstice; indeed, some have said that the Aethiopian Nile took from Sirius its name Siris, although others consider the reverse to be the case. Minsheu, who dwells much on this, ends thus:

Some thinke that the Dog-starre is called Sirius, because at the time the Dogge-starre reigneth, Nilus also overfloweth as though the water were led by that Starre.”

Indeed, it has been fancifully asserted that its canine title originated in Egypt, “because of its supposed watchful care over the interests of the husbandman; its rising giving him notice of the approaching overflow of the Nile.”

Caesius cited for it Solechin as from that country, signifying the Starry Dog, and derived from the Egypto-Greek word Soleken.

{Page 125} Perhaps it is the ancient importance of this Dog on the Nile that has given the popular name, the Egyptian X, to the figure formed by the stars Procyon and Betelgeuze, Naos and Phaet, with Sirius at the vertices of the; two triangles and the centre of the letter. On our maps Sirius marks the nose of the Dog.

The Phoenicians are said to have known it as Hannabeah, the Barker.

The astronomers of China do not seem to have made as much of Sirius as did those of other countries, but it is occasionally mentioned, with other stars in Canis Major, as Lang Hoo; and Reeves quoted for it Tseen Lang, the Heavenly Wolf. Their astrologers said that when unusually bright it portended attacks from thieves.

Some have called it the Mazzaroth of the Book of Job; others the H-asil of the Hebrews; but this people also knew it as Sihor, its Egyptian name, and Ideler thinks that the adoration of the Serim (Sirim), or “Devils” of the Authorized Version of our Bible, the “He Goats” of the Revision, which, as we see in Leviticus xvii, 7, was specially prohibited to the Jews, may have had reference to Sirius and Procyon, the Two Sirii or Shi’rayan, that must have been well known to them in the land of their long bondage as worshiped by their taskmasters.

The culmination of this star at midnight was celebrated in the great temple of Ceres at Eleusis, probably at the initiation of the Eleusinian mysteries; and the Ceans of the Cyclades predicted from its appearance at its heliacal rising whether the ensuing year would be healthy or the reverse. In Arabia, too, it was an object of veneration, especially by the tribe of Kais, and probably by that of Kodha’a, although Muhammad expressly forbade this star-worship on the part of his followers. Yet he himself gave much honor to some “star” in the heavens that may have been this.

In early astrology and poetry there is no end to the evil influences that were attributed to Sirius. Homer wrote, in Lord Derby’s translation,

The brightest he, but sign to mortal man

Of evil augury.

Pope’s very liberal version of the same lines, —

Terrific glory ! for his burning breath

Taints the red air with fevers, plagues and death, —

seems to have been taken from the Shepheards Kalendar for July:

The rampant Lyon hunts he fast with dogge of noysome breath

Whose baleful barking brings in hast pyne, plagues and dreerye death.

Spenser, however, was equally a borrower, for we find in the Aeneid

{Page 126} The dogstar, that burning constellation, when he brings drought and diseases on sickly mortals, rises and saddens the sky with inauspicious light;

and in the 4th Georgic

Jam rapidus torrens sitientes Sirius Indos Ardebat coelo

rendered by Owen Meredith in his Paraphrase on Vergil’s Bees of Aristaeus:

Swift Sirius, scorching thirsty Ind,

Was hot in heaven.

Hesiod advised his country neighbors,

“When Sirius parches head and knees, and the body is dried up by reason of heat, then sit in the shade and drink,”

— advice universally followed, even till now, although with but little thought of Sirius. Hippocrates made much, in his Epidemics and Aphorisms, of this star’s power over the weather, and the consequent physical effect upon mankind, some of his theories being current in Italy even during the last century; while the result of all physic depended upon the sign of the zodiac in which the sun chanced to be. Manilius wrote of Sirius:

From his nature flow

The most afflicting powers that rule below.

But these expressions as to the hateful character of the Dog-star may have been induced in part from the evil reputation of the dog in the East.

Its heliacal rising, 400 years before our era, corresponded with the sun’s entrance into the constellation Leo, that marked the hottest time of the year, and this observation, originally from Egypt, taken on trust by the Romans, who were not proficient observers, and without consideration as to its correctness for their age and country, gave rise to their diescaniculariae, the dog days, and the association of the celestial Dog and Lion with the heat of midsummer. The time and duration of these days, although not generally agreed upon in ancient times, any more than in modern, were commonly considered as beginning on the 3d of July and ending on the 11th of August, for such were the time and period of the unhealthy season of Italy, and all attributed to Sirius. The Greeks, however, generally assigned fifty days to the influence of the Dog-star. Yet even then some took a more correct view of the matter, for Geminos wrote:

It is generally believed that Sirius produces the heat of the dog days; but this is an error, for the star merely marks a season of the year when the sun’s heat is the greatest.

But he was an astronomer. {Page 127} The idea prevailed, however, even with the sensible Dante in his “great scourge of days canicular” while Milton, in Lycidas, designated it as “the swart star.” And the notion holds good with many even to the present time. This character doubtless is indicated on the Farnese globe, where the Dog’s head is surrounded with sun-rays.

But Pliny took a kinder view of this star, as in the “xii. chapyture of the xi. booke of his naturall hystorie,” on the origin of honey:

This coometh from the ayer at the rysynge of certeyne starres, and especially at the rysynge of Sirius, and not before the rysynge of Vergiliae (which are the seven starres cauled Pleiades) in the sprynge of the day;

although he seems to be in doubt whether “this bee the swette of heaven, or as it were a certeyne spettyl of the starres.” This idea is first .seen in Aristotle’s History of Animals. So, too, in late astrology wealth and renown were the happy lot of all born under this and its companion Dog. Our modern Willis wrote in his Scholarof Thebet ben Khorat

Mild Sirius tinct with dewy violet,

Set like a flower upon the breast of Eve.

When in opposition Sirius was supposed to produce the cold of winter.

It has been in all history the brightest star in the heavens, thought worthy by Pliny of a place by itself among the constellations, and even seen in broad sunshine with the naked eye by Bond at Cambridge, Massachusetts, and by others at midday with very slight optical aid; but its color is believed by many to have changed from red to its present white. This question recently has been discussed, by See in the affirmative and Schiaparelli in the negative, at a length not allowing repetition here, the weight of argument, however, seeming to be against the admission of any change of color in historic times.

Aratos’ term poikilos, applied to the Dog (constellaton), is equally appropriate to Sirius now in the sense of many-colored or changeful, and is an admirable characterization, as one realizes when watching this magnificent object coming up from the horizon on a winter evening. Tennyson, who is always correct as well as poetical in his astronomical allusions, says in The Princess

The fiery Sirius alters hue

And bickers into red and emerald;

this, of course, being largely due to its marked scintillation; and Arago gave Barakish as an Arabic designation for Sirius, meaning Of a Thousand {Page 128} Colors; and said that as many as thirty changes of hue in a second had been observed in it. [Montigny’s scintillometer has marked as many as seventy-eight changes in a second in various white stars standing 30° above the horizon, though a somewhat less number in those of other colors.]

Sirius, notwithstanding its brilliancy, is by no means the nearest star to our system, although it is among the nearest; only two or three others having, so far as is yet known, a smaller distance. Investigations up to the present time show a parallax of 0″.39, indicating a distance of 8.3 light years, nearly twice that of alpha Centauri.

Some are of the opinion that the apparent magnitude of Sirius is partly due to the whiteness of its tint and its greater intrinsic brilliancy; and that the red stars, Aldebaran, Betelgeuze, and others, would appear much brighter than now if of the same color as Sirius; rays of red light affecting the retina of the eye more slowly than those of other colors. The modern scale of magnitudes that makes this star — 1.43, — about 9½ times as bright as the standard 1st-magnitude star Altair (alpha Aquilae), — would make the sun — 25.4, or 7000 million times as bright as Sirius; but, taking distance into account, we find that Sirius is really forty times brighter than the sun.

Its spectrum, as type of the Sirian in distinction from the Solar, gives name to one of the four general divisions of stellar spectra instituted by Secchi from his observations in 1863-67; these two divisions including nearly (eleven twelfths) of the observed stars. Of these about one half are Sirian of a brilliantly white colour, sometimes inclining towards a steely blue. The sign manual of hydrogen is stamped upon them with extraordinary intensity by broad, dark shaded lines which form a regular series.

It is found by Vogel to be approaching our system at the rate of nearly ten miles a second, and, since Rome was built, has changed its position by somewhat more than the angular diameter of the moon. It culminates on the 11th of February.

The celebrated Kant thought that Sirius was the central sun of the Milky Way; and, eighteen centuries before him, the poet Manilius said that it was “a distant sun to illuminate remote bodies,” showing that even at that early day some had knowledge of the true character and office of the stars.

Certain peculiarities in the motion of Sirius led Bessel in 1844, after ten years of observation, to the belief that it had an obscure companion with which it was in revolution; and computations by Peters and Auwers led Safford to locating the position of the satellite, where it was found as {Page 129} predicted on the 31st of January, 1862, by the late Alvan Clark, at Cambridgeport, Mass., while testing the I8½-inch glass now at the Dearborn Observatory. It proved to be a yellowish star, estimated as of the 8½ magnitude, but difficult to be seen because of the brilliancy of Sirius, and then 10″ away; this diminishing to 5″ in 1889; and last seen and measured by Burnham at the Lick Observatory before its final disappearance in April, 1890. Its reappearance was observed from the same place in the autumn of 1896 at a distance of 3″.7, with a position angle of 195°. It has a period of 51½ years, and an orbit whose diameter is between those of Uranus and Neptune; its mass being one third that of Sirius and equal to that of our sun, although its light is but one 10, 000 nth its principal. So that it may be supposed to be approaching non-luminous solidity, — one of Bessel’s “dark stars.”

It is remarkable that Voltaire in his Micromegas of 1752, an imitation of Gulliver’s Travels, followed Dean Swift’s so-called prophetic discovery of the two moons of Mars by a similar discovery of an immense satellite of Sirius, the home of his hero. Swift, however, owed his inspiration to Kepler, who more than a century previously wrote to Galileo:

I am so far from disbelieving ill the existence of the four circumjovial planets, that I long for a telescope to anticipate you, if possible, in discovering two round Mars (as the proportion seems to me to require), six or eight round Saturn, and perhaps one each round Mercury and Venus.

Other stars are shown by the largest glasses in the immediate vicinity of Sirius, two additional having very recently been discovered by Barnard at the Yerkes Observatory.

Star Names, Their Lore and Meaning, Richard Hinckley Allen, 1889].